|

Our August 25th Cracker Barrel session dealt with local experiences during World War II, and the resulting discussion between panel members and attendees awakened many memories about life during that trying period. Panelists, and WW II vets, Bob Masten and Charlie Mange recounted the perils of that war through their experiences on the European and Pacific fronts, respectively, but, the main discussion centered upon adjustments and sacrifices that were experienced here on the home front.

In Arcadia, as throughout the Nation, life changed drastically after Japan’s bombing attack on Pearl Harbor December 7, 1941. The long debate about entering the world conflict was over; we were at war with Japan. On December 11 Hitler and Mussolini followed with their declaration of war on the United States, so, without choice, we had also joined the Allies in the war against Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. There was a sudden sense of urgency throughout the Nation. Our Government—and even Hollywood—encouraged it. All focus had to be on war production and supplying the needs of our fighting men. There truly was a feeling of “We will do without so that they will have enough.”

|

“We will do without so that they will have enough.

|

|

Japan had already conquered areas in the Dutch East Indies which were U.S. sources for rubber, silk, and floss from Kapok trees, so there was immediate concern about shortages of these products. In early 1942 the federal government began a system of rationing for common everyday products, and rubber was the first nonfood product on the list. Ration books and tokens were issued to American families which controlled the amount of gasoline, tires, sugar, meat, leather, silk, and other consumer items each person could buy. Car owners around Arcadia soon learned just how bald a tire could get before it blew—and how to use the handy patching kit when it finally did. We kids growing up on the surrounding farms soon learned that just one teaspoon of sugar could make our morning oatmeal sweet enough. And, anyone who ever sampled it would not forget the white, lardy oleo (oleomargarine) that was introduced to replace butter. After public disgust, the company responded with packs of yellow dye which you mixed-in to make it resemble butter. That helped psychologically, but early oleo was, indeed, unforgettable.

Michigan, with Detroit being the automobile capital of the Nation, had to play a major part in the war. Civilian car production ceased in February 1942 as auto assembly lines retooled for military production. Before it was over, Michigan would receive $21 billion of the $200 billion in war contracts, second only to New York. Ford’s Willow Run plant alone would produce 8685 B-24 bombers, and Chrysler would manufacture over 25,000 tanks. It was later said that this was the greatest industrial transformation in all of history. During the war, over a half million people moved from the South to fill the jobs in Detroit. With the many thousands of our Nation’s young men entering military service, women needed to step in quickly and fill the surging war plants workforce. They quickly became the electricians, welders, and riveters. It was the beginning act of “Rosie the Riveter.” By 1943, women made up 65% of the aviation industry work force. The unemployment rate in Michigan almost vanished and capita income increased 115%. Having just survived the long years of the Great Depression, Michiganders were finding the times incredible.

|

Willow Run Bomber Plant

March 3, 1943. Rosie the RIveter worked here to help Ford produce thousands of B-24 Liberator bombers.

-- Associated Press. May 1, 2014.

|

|

Thousands of tons of steel were needed for the massive requirements of this war. Though steel production was upped to near its max, shortages were still feared, so nation-wide drives for scrap metal were put in place and highly promoted. Unlike recycled aluminum and rubber, which were subsequently found to be inadequate for making aircraft and tires respectively, scrap steel could be easily melted and reused. Arcadia did its share. Paul Scheppelman and Jerry Schroeder, 1949 grads of Arcadia High School, had remembrances of collecting that metal. Paul said their family farm on Steffens Road, where his dad also operated a metal salvage yard, was a chosen spot for assembling all kinds of war materials—rags, paper, and metal. When they acquired enough for a load, it was taken to the Manistee railway where the Miller Brothers, Sam and Hiemie (a salvage company), would have a waiting box car. When the box car became full, it was railed to the Detroit melting plants.

Classmate Jerry remembers, as other former students do, that the town also had a scrap collection place on the corner of the present “Finch Park.” Jerry grew up down the way on Fifth Street. Many dropped their old metal there, but, since Miller Brothers would pay “a little something” for good scrap steel, he and his dad, Otto, would often haul theirs directly to Manistee. In Depression times, one or two dollars meant a lot. Like a leftover reminder of those times, Hiemie’s son, Sam Miller Jr. still resides in Manistee.

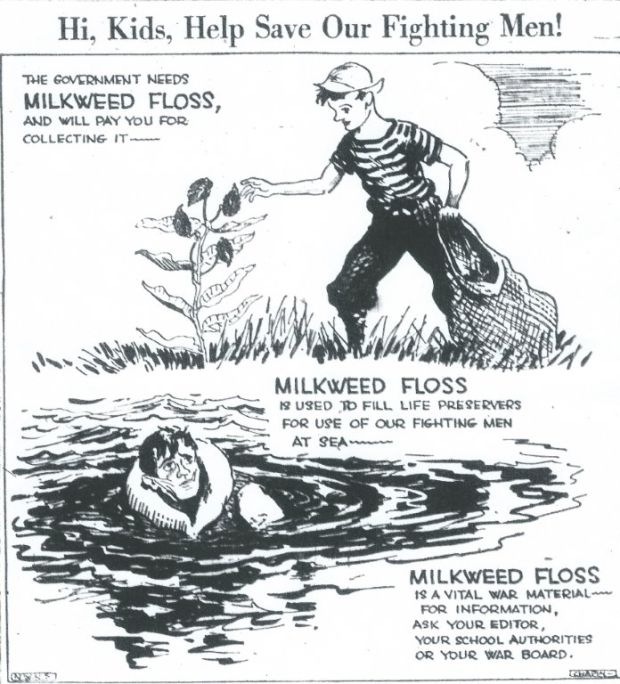

Both Paul and Jerry also remember the vital milkweed project of 1944. After Japan conquered the Dutch East Indies region, America lost its access to the Kopak trees which had provided the floss needed for making floatation devices. Life jackets and floatation wear were essential for our sailors and airmen. A substitute material had to found. The wispy floss of the milkweed pod was the answer. If picked when the pod seeds were brown and dry, the floss provided great buoyancy. Once dried and packed, one and three quarters pounds could keep a man afloat for hours. The Government estimated there was a need for two million pounds, enough to fill 1.2 million life jackets. It would have taken three years to cultivate a commercial crop, so there was a great appeal to schools and students to gather pods from the wild plants.

Project officials provided schools with 50# onion skin bags and instructions about when and how to pick and store the pods. Paul said they used their barn for the hanging and drying. Supposedly kids could earn 15 cents a bag for full 15# bags, but, Paul’s wife, Marie (Hull), remembers getting only 10 cents a bag. When they announced the project in our little country school just off M22 on Joyfield Road, we kids envisioned getting semi rich. Our cow pastures were full of these obnoxious milkweeds. A hundred bags would be an unimaginable fifteen dollars. Turns out, of course, it took a lot of pods to fill those expanding bags, and our small hands were much slower than we thought. Portions of those pastures were sparser than imagined. When they finally came to pick up our (less than 30) drying bags, we were deducted for some “too green and wetness” and “less than full bags.” So, there’d be no Red Ryder BB gun that year, but, Mr. Goodbars and big ice cream cones were still only a nickel at Marie Arnold’s store on Herring flats—all was well enough. It was the Depression after all.

|

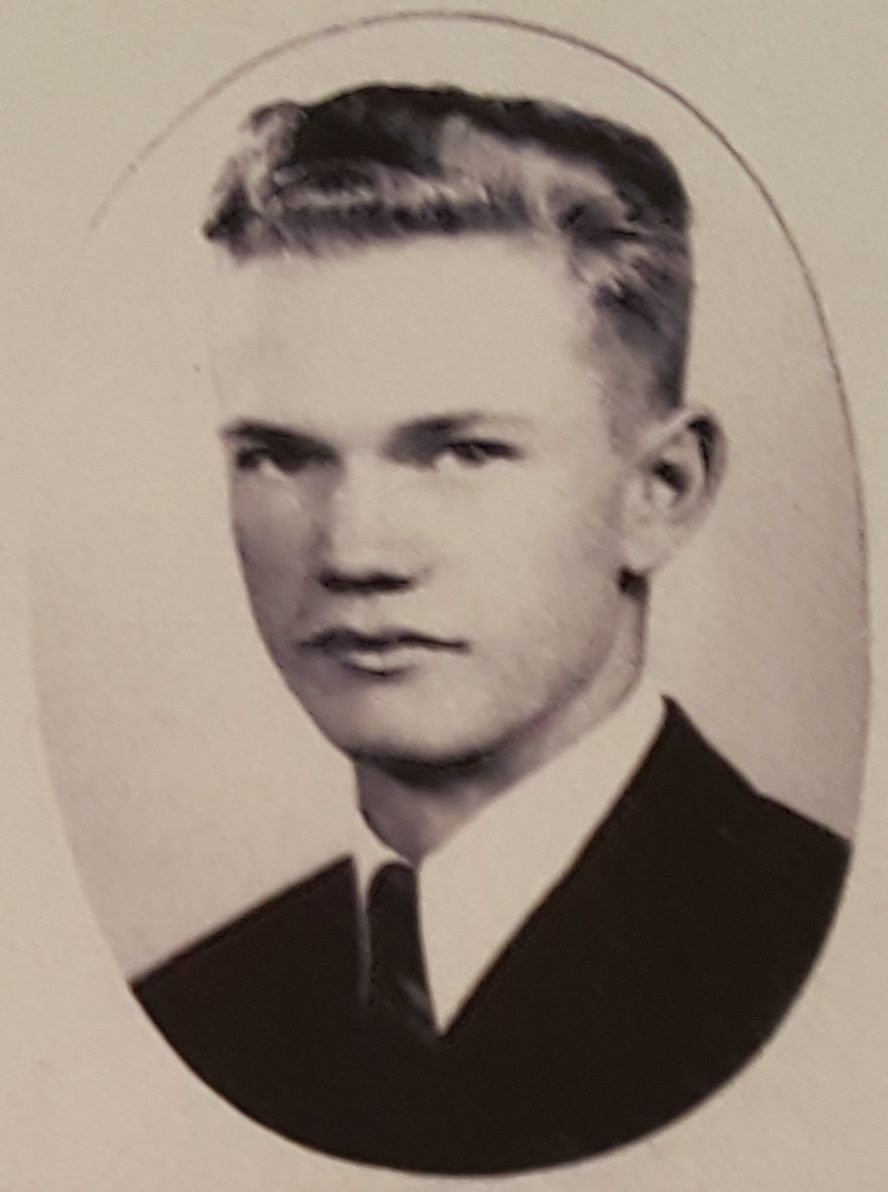

Paul Scheppelman

1949 Class Photo

Jerry Schroeder

1949 Class Photo

|

|

Overall, the milkweed project was a great success. An estimated eleven million pounds were gathered during the war. About 60 percent of the floss had come from Emmett County and the surrounding area. The main plant for drying and processing the pods, The Milkweed Floss Corporation of American, had been built in Petoskey in 1943. In 1945, we were all ready to gather again, but, the need was gone and the crop went unharvested.

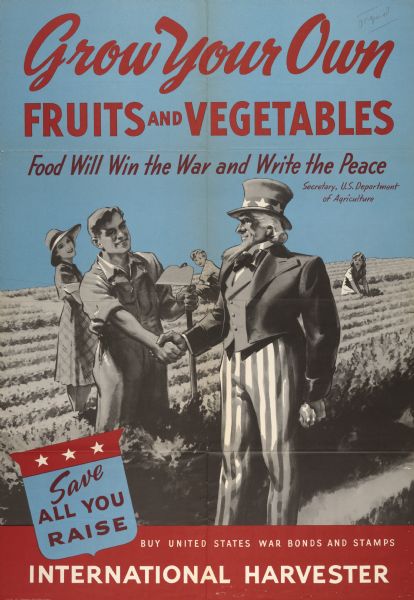

Another wartime program, Victory Gardens, was one also conducted much through the schools. In and around Arcadia, most folks were already growing gardens, but this program did successfully spread into even city areas where citizens were using small backyards and even window planters to raise vegetables. It is estimated that over 20 million gardens were actually planted and that one year 40% of all vegetables grown in the U.S. came from Victory Gardens. In our country school we were allotted two packs of seeds each. Since my mother always planted a huge vegetable garden anyway, I frivolously chose watermelon and Zinnia seeds. But, to this day, I still love watermelon and favor Zinnia flowers.

For those of us who lived through those times, the deepest memories are those of seeing family and friends go off to war. Still etched in my mind is the October day in 1943 when Mom, Dad, and I bid my brother Bob goodbye from the Thompsonville train station. Our anxiety would finally end on a happier note; after 67 missions as a B-26 gunner over France and Germany, Bob would return home on furlough in June, 1945. Thankfully, the vast majority of Arcadia grads who served would also come home. It was a sadder story for one of Bob’s Arcadia H.S. classmates (and our country neighbor), Charlie Hunt. Charlie, an infantryman, would lose his life during one of the major Pacific island invasions.

|

War Effort Poster

--Westby Times. Aug. 2, 1944

Collecting Milkweed Pods

Children were recruited for pod picking. The boy on the right shows a milkweed-stuffed life jacket.

-- MLIVE.COM. Feb 3, 2014. Photo courtesy of Milne Special Collections and Archives Department, University of New Hampshire Library.

Victory Garden Poster

WWII era poster promoting victory gardens and war bonds.

-- International Harvester. 1943.

|

|

Memorable to me, on his last, and probably only, furlough in March, 1943, Charlie Hunt was asked to do a little evening presentation at our country school. It had been arranged by Ivan Frain, a parent who then lived on Joyfield Road—just beyond Hunt Road (upon which Charlie was born). Our school never had electricity, so Charlie talked, as with all our evening programs, under the quaint light of kerosene lamps. Neighbors from miles around were there. Charlie described in some detail the training he had just completed in the swamps of Louisiana. I won’t forget his describing the “chiggers” that would invade their sleeping bags and burrow into their skin at night. Ivan had him end the talk with a little “manual of arms” display—using an M1 rifle. It was long afterward that I realized, in days gone by, Charlie would have also attended this very school.

In a final, happier thought on how WW II changed lives or determined futures, many still remember one of Arcadia’s early auto mechanics, Louie Johnson. When civilian auto production halted during the war, it was a must to keep the old cars running. Mechanics like Louie were in demand. Early in the war, Louie moved his family from Dry Hill to the vacant Luther Gilbert house north of Arcadia on M22. There in an old shed-like garage he started a serious auto and tractor repair business. Many a young man in the forties and fifties remember relying on Louie to keep their “junkers” going. Well, Louie passed his skills down to all his sons, but, son Eddie would eventually build his own, “big” garage a little further north on 22. There he ran a major truck and auto repair service. Eddie passed away way too soon, but, his son, Art, who carried on his dad’s business, has expanded it to a whole new level. And, judging from the second huge garage he has just built, Art intends to extend Grampa Louie’s business into even another generation.

|

Charles Hunt

|